|

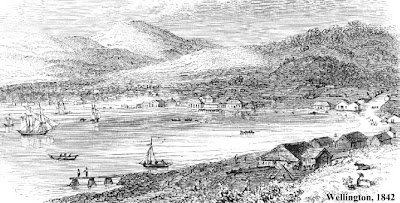

| Wellington Harbour, from Johnson's Hill. |

Wellington City curves in a gentle arc around its waterfront, a vast public playground that's the envy of many other cities. Because of its almost land-locked harbour and its position on the southern tip of the North Island, Wellington has always been a maritime city and I think it always will be.

|

| Sculptures make the waterfront an attractive and engaging place, but imagine a tall ship here! |

On any fine day, the waterfront is thronged with walkers, runners, cyclists, skaters, rowers, fishers, swimmers, diners, and sightseers, all enjoying the cafes,

museums, sculptures, wildlife, and the shipping. But it doesn't have two facilities that many other waterfront cities enjoy: an aquarium and a tall ship.

|

| Insert tall ship here. |

Others have been busy working towards an aquarium, and although it looks like it's not going to happen on the waterfront it is happening. But for a while now I've been musing about a tall ship for Wellington. I don't have the personality or the connections to drive such a project, but after a few years of dreaming about this, I thought the least I could do was to write a blog post and put the idea out there.

Tall ships visit here from time to time of course, and in the old days the harbour was full of them (above). In recent years the

Spirit of New Zealand and the Spirit of Adventure have been occasional visitors, and the replica

Endeavour and several naval training ships have paid us a call, to great public interest and enthusiasm. Now I think it's time the capital city had a tall ship of its own.

|

| The Endeavour replica in Wellington Harbour. |

Our tall ship would be a link with our city's 19th century origins and would emphasize our maritime environment. It'd be ideal to have a replica of one of our first immigrant ships, such as the

Aurora. The

Aurora was a one of class of elegant ships called "

Blackwall Frigates". There are plans available for the

class, if not for the

Aurora itself. Wouldn't it be an adventure to build it in New Zealand!

|

| La Hogue, a Blackwall Frigate (The Illustrated London News', August 11th, 1855) |

Our tall ship would be a tourist attraction. It would add so much to the atmosphere of the waterfront, and it could be self-funding through cruises, much as tall ships are all over the world. In my mind I can see it moored outside

Te Papa.

Tall ships everywhere often double for youth leadership and confidence training. That's a role Wellington could value too. Sailing such a ship in Cook Strait has got to be character-building. The Spirit of Adventure Trust has included Wellington youngsters on its cruises, but its ship

Spirit of New Zealand is based in Auckland.

Last but not least, it'd simply be cool.

How much would a tall ship cost?

I've no doubt that building a replica

Aurora would be an expensive proposition well into the tens of millions, but doing it would provide training and employment here in Wellington so a fair proportion of that cost would find its way back into our economy. Buying an existing ship would be cheaper, although it wouldn't have the historical links with the city. Look at this lovely steel

brig for example: the asking price of 4.3 million euros would leave a little change out of NZ$7M. That's not too bad.

Who would pay for it?

Personally, I don't believe it's the city council's role to bankroll items like this, but the council does support other projects, especially when they are tourist attractions or provide employment in the region. Public subscription is another option, with different classes of donors promised something back: maybe a cruise if you give $2000, a free visit if you give $200 or pay an annual subscription to a trust. There are probably groups in the city, service clubs and the like, who would willingly raise funds. And corporate donations and sponsorship should be welcomed; at least one I can think of already has a close relationship with Wellington's winds. Ideally, the ship would be self-supporting once purchased, but that might not be realistic. There's plenty of experience around the world of running tall ships, and no doubt lots of enthusiastic people who'd be happy to help us get started.

So what do you think? If you like the idea, pass it along by word of mouth and social media, comment below, or just click the "cool" box at the bottom of this article. Let's get Wellington's wind in our sails!

.jpg) |

| Mast, top, shrouds, and yard. Endeavour replica. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)